Use of the laterally closed tunnel technique for the treatment of a single deep mandibular recession

Machine translation

Original article is written in ES language (link to read it).

Summary

Gingival recession is defined as the displacement of the gingival margin in the apical direction from the cemento-enamel junction. It is a very common problem even in patients with good oral hygiene, and it occurs in both the maxilla and the mandible and on one or multiple root surfaces.

In the international literature, the satisfactory treatment of gingival recessions through multiple mucogingival techniques is well documented. This clinical case presents a technique based on the novel approach of the laterally closed tunnel. Additionally, amelogenins will be used to promote healing and periodontal regeneration.

Introduction

Gingival recession is defined as the displacement of the gingival margin apical to the cemento-enamel junction. It is a very common problem even in patients with a high standard of oral hygiene, both in the maxilla and in the mandible, or on one or multiple root surfaces (American Academy, 1996).

The main indications for the treatment of these defects, according to what was agreed upon at the first European Periodontology Meeting in 1994, include aesthetics, hypersensitivity, or hygienic-orthodontic situations. International literature has often documented that gingival recessions can be satisfactorily treated using multiple mucogingival techniques.

Clinical experience shows us that more and more patients present multiple or isolated recessions due to various local factors, whether it be the anatomy of the tooth or its position. Particularly common are single recessions in the area of the mandibular incisors. This problem has been extensively studied and has been found to be especially present in areas with a thin buccal plate or a thin gingival biotype. This predisposition, combined with inefficient and unfortunate plaque control, can lead to this issue.

The technique we present in this article is a very interesting and effective approach for those isolated deep recessions in the mandibular lower incisors. Traditionally, gingival recessions have been treated with a free gingival graft of epithelial and connective tissue. Over time, it has been observed that the healing of this type of graft yielded good results in terms of gain of keratinized attached gingiva, but not so favorable in terms of aesthetics (color change, shape, etc.) and complete root coverage.

We can classify this technique, based on its blood supply, as a monolaminar technique, since it receives vascularization only from the periosteum. Bilaminar techniques, on the other hand, are those that receive vascularization from both the basal periosteal part and the part of the flap that covers it. Among the bilaminar techniques, we find coronal or lateral repositioning flaps, subepithelial connective tissue grafts, guided tissue regeneration, and tunnel techniques for one tooth or for several teeth.

Bilaminar techniques opened a new era in the treatment of gingival recessions, and among their advantages are good aesthetics and a higher percentage of root coverage.

However, it is often a treatment that requires releases and is not very reproducible because we have to work through layers of gum (partial thickness, periosteum, etc.).

For these reasons, less invasive tunnel techniques have emerged with less risk of tearing soft tissue. Sculean et al. presented a novel technique in 2018, the laterally closed tunnel, in which the approximation of the edges with connective tissue graft in a tunnel has proven to be very effective and predictable.

In this clinical case, a technique based on the laterally closed tunnel is presented, with a small modification for those cases where, for anatomical reasons, maintaining the gum without tension near the cementoenamel junction is complicated. Additionally, amelogenins (Emdogain®, Straumann®) were used to promote healing and periodontal regeneration.

Case Presentation

This is the case of a 28-year-old young woman, categorized as ASA I on the preoperative risk index of the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) (Maloney et al. 2008), who presented with a Miller Class II recession and Cairo RT1, unique and deep, on the tooth. The patient was a non-smoker and showed oral hygiene with a plaque index of less than 25% and a bleeding index of less than 10%.

Upon examination, a thin biotype was noted and the probing depth was 4 mm in almost all teeth. In the weeks prior to the intervention for the recession, a prophylaxis treatment with ultrasound was performed. The recession did not present interproximal bone loss or increased pocket depth in the radiographic study.

The objective of the treatment was to restore aesthetics with complete root coverage and better plaque control for the patient. The proposed technique was a modification of the bilaminar technique with laterally closed tunnel. Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Development of the intervention

After infiltrative anesthesia with articaine at the bottom of the vestibule, the decontamination of the root portion exposed to the oral environment was performed using curettes and periosets (26.1).

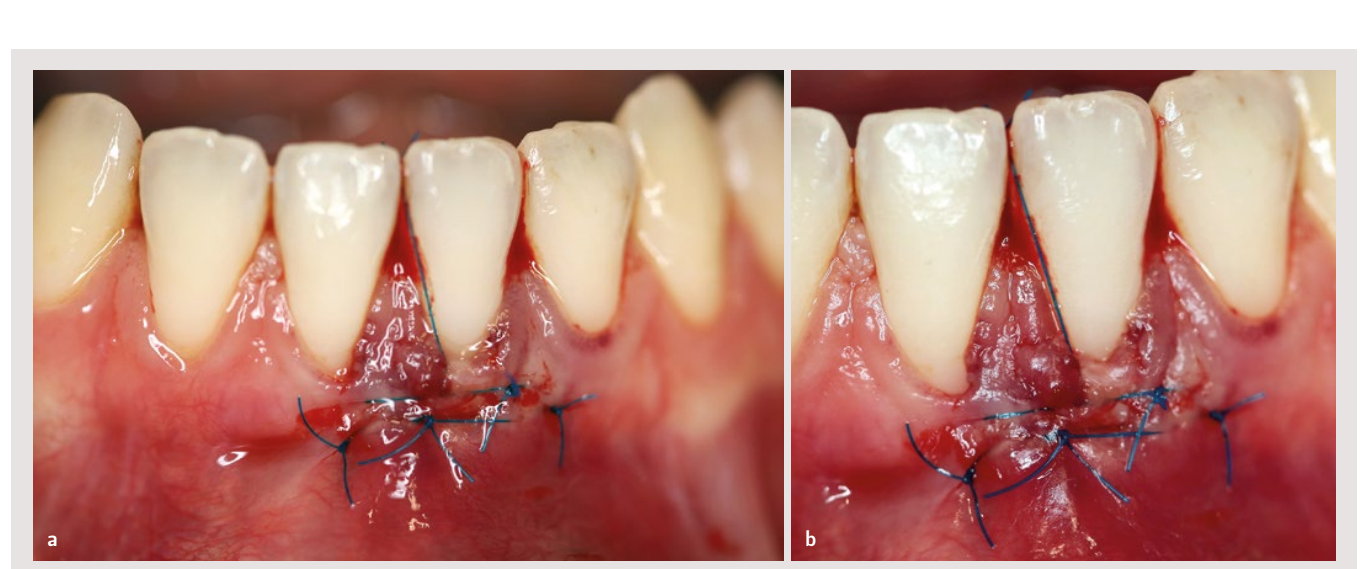

Next, an intrasulcular incision was made with a microsurgery scalpel, and with specific instruments, it was carefully tunneled. In these cases, the instrument must reach the mucogingival line and surpass it apically and laterally (mesial and distal), and coronal displacement of the papillae must be achieved. The apical and lateral muscle fibers must be released using the micro scalpel (micro blades, Keydent) and Gracey curettes (Stoma®) until a passive release of the margin is achieved (26.2).

Great care must be taken not to tear the tissues or the papillae to avoid creating areas of necrosis. This technique allows for the approximation of the mesial and distal edges until the root is covered.

Once the recipient bed was prepared, a graft of epithelial and connective tissue obtained from the palate was placed, from which the epithelium had been removed with a micro-scalpel (26.3).

Next began the delicate phase of graft stabilization, and for this, it was sutured with 6-0 sling suture in a tunnel adapted to the cementoenamel junction. Subsequently, the mesial and distal edges of the margin were sutured together. The modification of the laterally closed tunnel technique, in this case, consisted of providing a suspensory point from apical to interproximal of the teeth to maintain coronal advancement and eliminate tension on the graft during the healing period (26.4).

For 10 minutes, before placing the graft and after suturing, amelogenins were applied to promote the healing of periodontal tissue. The reason for using these proteins is their potential for regeneration and improvement of pocket depth (26.5).

As postoperative measures, the use of antibiotics (amoxicillin 750 mg with 125 mg of clavulanic acid), an analgesic (ibuprofen 600 mg), and 0.12% chlorhexidine for 14 days was prescribed. The patient was instructed not to pull on the lip and not to brush the area.

The patient returned after a week for a check-up and after 15 days for suture removal. During the 6-month follow-up, the stability of the graft and ongoing maturation in the treated area were observed. A 100% coverage was achieved with 4 mm of coverage compared to the starting point (26.6).

Annual check-ups were scheduled to verify the maturation of the tissues and the effect of migration or creeping attachment.

Discussion

In this clinical case, a novel technique has been presented to predictably cover isolated mandibular unit recessions. According to Sculean et al., with this technique, the mean depth of gingival recession changes from 5.14 ± 1.26 mm at baseline to 0.2 ± 0.37 mm at 12 months, while the mean root coverage reaches 4.94 ± 1.19 mm (p < 0.0001), representing a 96.11% coverage of the initial recession. In this study, Miller class I, II, and III recessions were treated, and an optimal result was confirmed in the most unfavorable cases, as complete root coverage was achieved in 60% of the cases. In a randomized controlled study, Zucchelli et al. evaluate the treatment of Miller classes I and II through coronal advancement with and without the removal of submucosal tissue, with a statistically significant result in the reduction of graft exposure and an increase in root coverage from 48% to 88%. These data highlight the importance of relieving tensions and creating a passive flap to achieve better root coverage outcomes. Hence, the modification with a suspensory suture to maintain the flap in position helps to reduce, especially in Miller class III, the tension of the flap.

Numerous studies have shown that the use of a connective tissue graft plays a key role in stabilizing the clot and providing the necessary cells for the regeneration and keratinization of soft tissues.

The connective tissue graft close to the subepithelial layer has the greatest capacity to induce keratinization; on the other hand, a thickness not exceeding 1 mm reduces tissue contraction and postoperative morbidity. The tension-free suture of the flap in a coronal position at the cementoenamel junction reduces the risk of exposure of the connective tissue graft.

Various systematic reviews show that the use of bilaminar techniques along with connective tissue grafts and enamel-derived proteins (amelogenins) increases the predictability of root coverage and the gain in clinical attachment level.

The efficacy of the topical use of enamel-derived proteins has been demonstrated in terms of healing and periodontal regeneration, as it induces the creation of periodontal tissues (for example, periodontal ligament, root cementum, and alveolar bone). Human biopsies have confirmed this. However, the lack of a protocol and better scientific evidence necessitates more studies on this matter.

Finally, it is important to highlight that any periodontal surgery treatment, including mucogingival surgery, is extremely dependent on the operator and the patient, and the responsibility for achieving a satisfactory final result lies with the professional who performs it, knowing how to develop a good treatment plan based on the characteristics of their patient and providing them with the correct postoperative maintenance measures.

Conclusions

With the inherent limitations of a clinical case, we can confirm that the modified laterally closed tunnel technique that has been employed is a valid and safe technique for the patient, which reduces morbidity and increases predictability when achieving complete root coverage in the treatment of isolated mandibular gingival recessions of types I, II, and III according to Miller.

Bibliography

- Guinard EA, Caffesse RG. Treatment of localized gingival recessions. Part I. Lateral sliding flap. J Periodontol. 1978;49:351-356.

- Miller PD. A classification of marginal tissue recession. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1985;5:8-13.

- Allen AL. Use of the supraperiosteal envelope in soft tissue grafting for root coverage. I: Clinical results. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 1994;14:216-227.

- Burkhardt R, Lang NP. Fundamental principles in periodontal plastic surgery and mucosal augmentation - a narrative review. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:S98-S107.

- Freedman AL, Green K, Salkin LM, Stein MD, Mellado JR. An 18-year longitudinal study of untreated mucogingival defects. J Periodontol. 1999;70:1174-1176.

- Sullivan HC, Atkins JH. Free autogenous gingival grafts I. Principles of successful grafting. Periodontics. 1968;6:121- 129.

- Cortellini P, Tonetti M, Baldi C, Francetti L, Rasperini G, Rotundo R, Nieri M, Franceschi D, Labriola A, Prato GP. Does placement of a connective tissue graft improve the outcomes of coronally advanced flap for coverage of single gingival recessions in upper anterior teeth? A multi-centre, randomized, double-blind, clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2009 Jan;36(1):68-79.

- Grupe HE, Warren RF. Repair of gingival defects by a sliding flap operation. J Periodontol. 1956;27:92-99.

- Langer B, Langer L. Subepithelial connective tissue graft-technique for root coverage. J Periodontol. 1985;56:715-720.

- Tinti C, Vicenzi G, COCCHETTO R. Guided tissue regeneration in mucogingival surgery. J Periodontol. 1993;64:1184- 1191.

- Zabalegui I, Sicilia A, Cambra J, Gil J, Sanz M. Treatment of multiple adjacent gingival recessions with the tunnel subepithelial connective tissue graft: a clinical report. Int J Pe- riodontics Restorative Dent. 1999:19:199-206.

- Harris RJ. Root coverage with connective tissue grafts: an evaluation of short and long term results. J Periodontol. 2002;73:1054-1059.

- Cairo F, Pagliaro U, Nieri M. Treatment of gingival recession with coronally advanced flap procedures: a systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2008;35:136-162.

- Sculean A, Allen E. The Laterally Closed Tunnel for the Treatment of Deep Isolated Mandibular Recessions: Surgical Technique and a Report of 24 Cases. The Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2018;38(4):479-487.

- Maloney WJ, Weinberg MA. Implementation of the American Society of Anesthesiologists Physical Status classification system in periodontal practice. J Periodontol. 2008 Jul;79(7):1124-6. doi: 10.1902/jop.2008.070625. PMID: 18597592.

- De Sanctis M, Zucchelli G. Coronally advanced flap: a modified surgical approach for isolated recession-type defects: three-year results. J Clin Periodontol. 2007;34:262-328.

- Cairo F, Nieri M, Pagliaro U. Efficacy of periodontal plastic surgery procedures in the treatment of localized gingival recessions. A systematic review. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:S44-S62.

- Zucchelli G, Mounssif I, Mazzotti C, Montebu-Gnoli L, Sangiorgi M, Mele M SM. Does the dimension of the graft influence patient morbidity and root coverage outcomes? A randomized controlled clinical trial. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:708–16.

- Chambrone L, Faggion C M, Pannuti CM, Chambrone LA (2010). Evidence-based periodontal plastic surgery: an assessment of quality of systematic reviews in the treatment of recession-type defects. J Clin Periodontol. 2010;37:1110-1118.

- Pini-Prato GP, Cozzani G, Magnani C, Baccetti T. Healing of gingival recession following orthodontic treatment: a 30-year case report. Int J Periodontics Restorative Dent. 2012 Feb;32(1):23-7. PMID: 22254220.

- Sculean A, Gruber R, Bosshardt DD. Soft tissue wound healing around teeth and dental implants. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:S6-S22.

- Zucchelli G. Clinical and anatomical factors limiting treatment outcomes of gingival recession: a new method to predetermine the line of root coverage J Periodontol. 2006;77:714-721.

- Pini Prato GP, Baldi C, Nieri M, Franceschi D, Cortellini P, Clauster C, Rotundo R, Muzzi L. Coronally advanced flap: the post surgical position of the gingival margin is an important factor of achieving complete root coverage. J Periodontol. 2005;76:713-722.

- Tonetti MS, Jepsen S. Clinical efficacy of periodontal plastic surgery procedures: Consensus Report of Group 2 of the 10th European Workshop on Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:S36-S43.

- Carnio J, Camargo PM, Kenny EB, Schenk RK. Histologic evaluation of 4 cases of root coverage following a connective tissue graft combined with an enamel matrix derivative preparation. J Periodontol. 2002;73:1534-1543.

- Sanz M, Simion M. Surgical techniques on periodontal plastic surgery and soft tissue regeneration: consensus report of Group 3 of the 10th European Workshop on Periodontology. J Clin Periodontol. 2014;41:S92-S97.

/social-network-service/media/default/101189/a4a762d0.png)